You can’t just blindly put money in a 401(k) and assume that once you’re retired, it’ll all turn out perfectly. Do you even know what’s in your 401(k), or how to determine what is? It’s okay to admit that you don’t, we’re all friends here and no one will judge you (except possibly me, and I can’t see you anyway.)

If you work at a company of a certain size, then sometime in your first year on the job, a representative from Smith Barney or Fidelity or Vanguard or somewhere came to your office and held a lunch meeting in the break room. She might have brought pad thai. There’s a good chance you weren’t even there: one-third of corporate employees who are eligible for 401(k)s don’t even take advantage of them. If you were there, you almost certainly weren’t paying attention when she handed out the prosaic brochures about her company offering several exciting financial products to cater to your retirement needs, blah blah blah. At this point, the people who are still listening usually defer to whatever the company rep or the company’s chief accountant recommends. Which isn’t necessarily going to cost you money, but it does mean you’re surrendering your financial decisions to someone else. Fortunately, it’s not that difficult to regain control of where your money’s going.

Your 401(k) almost certainly owns a piece of a mutual fund, or funds. No, the two terms aren’t synonymous. The mutual fund itself isn’t a retirement plan: it’s an agglomeration of investments, which is then divided into pieces small enough for regular people to own a piece of.

Say you wanted to buy Google stock, which is trading at $514.30 as I type this. A standard order of stock is 100 shares, meaning you’d need at least $51,430 to buy in. Do you have that kind of money sitting around? If you do, do you want to invest it in the least diverse of all securities (a single stock)?

Thus mutual funds. A typical mutual fund will contain millions of dollars’ worth of Google, maybe McKesson, some Anheuser-Busch, a dollop of General Electric and a light seasoning of Safeway, among dozens of others. The fund manager then makes pieces of the fund available to individual investors (and to 401[k]s), for as little as $250. Instead of buying 100 shares of Google, you can own .00078 shares. Easy street, here you come!

I know this already. Stop talking down to me.

Really? Then what’s in your 401(k)?

Uh…er…

Here’s how you find out. Find the investment management company that holds your 401(k). You should get statements from them regularly. If you toss them out, ask the relevant person at your office exactly what your 401(k) is in.

Vanguard’s big, let’s use them as an example. There’s a place on the front page of their website where you can view all their mutual funds. We did, and picked something called the Growth Equity Fund at random. Vanguard sells 118 funds, 18 of them classified as “Domestic Stock – more aggressive” funds, which the company describes as being for people who “(seek) maximum long-term total return, without significant dividend income,…(have an) investment horizon of (>5 years), (and/or are willing to) accept wide fluctuations in share price.”

Well, then.

At the relevant page, you’ll learn a couple of important things:

- the Growth Equity Fund’s holdings are worth about $562 million;

- .51% of the money the fund takes in goes to expenses;

- it has a ticker symbol, VGEQX, meaning you can track it daily on Yahoo! Finance or somewhere similar.

The page also lists the funds’ 10 biggest components. You know what that is? Almost useless, because it leaves ¾ of the fund unaccounted for. For the full picture, go to the “Portfolio & Management” tab and scroll down to the “portfolio holdings” link. It’ll list all 81 companies your 401(k) has a piece of, from Apple (which this fund owns about $32 million of), all the way down to Ritchie Bros. Auctioneers (about $1.6 million.) In order to stay liquid for emergencies, the fund also holds a couple of investments that are almost the equivalent of cash – $2.2 million in Freddie Mac discount notes and another $22 million in short term reserve holdings.

Most investment companies list the components by percentages, rather than raw umbers. In the case of Vanguard, you have to do a little division to know that VGEQX consists of about 5.7% Apple, 3.5% Cisco, 2.9% Microsoft…and .3% Ritchie Bros.

And hey…there’s that Google stock that’ll make you rich, about 1/3 of the way down, at 1.4%.

Look, 401(k)s are a great way to save for decades down the road. One of the features about 401(k)s people like is that they can “set-and-forget” them. But it’s not that simple.

Would you hire a nutritionist to feed you, then strap on a blindfold at mealtime every day, certain that whatever the nutritionist was putting in your mouthwas good for you? Maybe, but presumably you’d want to at least take a look yourself. The same should go for investments. You don’t want to check your 401(k) composition and how its components are doing every day, but bimonthly or quarterly won’t kill you. Especially since it’s so easy to do.

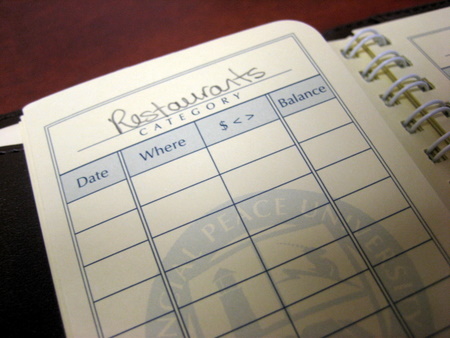

Greg McFarlane is an advertising copywriter who lives in Las Vegas and Lahaina. He recently wrote Control Your Cash: Making Money Make Sense, a financial primer for people in their 20s and 30s who know nothing about money. Buy the book here (physical) or here (Kindle) and reach Greg at greg@ControlYourCash.com.